COVID-19 vaccination tents are set up in the north of the Toy Story parking lot at the Disneyland Resort on Jan. 12, 2021, in Anaheim, California. (Orange County Register Photo via Getty Images/Photo by Jeff Gritchen)

Without resources or infrastructure from the federal government, the state-by-state approach has meant a slow, messy rollout. But that could change soon.

The United States is nearly a month into its COVID-19 vaccination efforts, and so far, things are not going according to plan.

The federal government, through its Operation Warp Speed vaccine program, aimed to provide 20 million Americans with their first dose of the vaccine in December. Instead, fewer than 9 million people have received their first shot as of Tuesday morning, despite more than 25 million doses being distributed across the country, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

So what gives? Why is the rollout such a mess? And how can it be fixed?

The problem, experts say, is multifaceted. As with virtually every other aspect of the pandemic response, the federal government has largely left vaccine distribution to the states without giving them the necessary funding and resources, resulting in scattershot plans, staffing shortages, a complex web of rules guiding who can get vaccinated, and in some cases, uncertainty over how many doses will arrive each week. State governments, which have struggled to create centralized sign-up systems and failed to communicate clearly, have also made their own blunders.

Experts hope President-elect Joe Biden’s promise to unveil a national vaccination plan will solve the nation’s vaccine woes, or at the very least, begin to build the infrastructure that has been so sorely lacking.

Federal Coordination and Infrastructure Is Absent

“The biggest hurdle for vaccine rollout is a lack of coordinated infrastructure,” Dr. Dara Kass, associate professor of emergency medicine at the Columbia University Medical Center, told COURIER. “Every state has to build its own infrastructure for communication and delivery of the vaccine.”

This means that each state has had to create its own plan, with its own communications, data, and organizational apparatus to get the vaccine from distributors and into patients’ arms. While hospitals, nursing homes, and medical centers have been able to use their institutional medical health records to schedule appointments and communicate with vaccine recipients, states and local public health departments have no such equivalent, which has slowed down the rollout, according to Dr. Kass.

This disjointed free-for-all has led to a wide range of outcomes with regards to how states’ vaccine efforts are going. Leading the way in terms of success are North Dakota, which has distributed 73% of its shots, and neighboring South Dakota, which has used 70% of its allotment, according to CDC data. On the opposite end of the spectrum, places like Arkansas and Georgia have used fewer than 20% of the doses they were sent.

Republicans Delay in Providing Funding Made a Herculean Task Even Harder

The most frustrating part, perhaps, is that these issues weren’t unexpected. State leaders and local public health officials warned for months before the rollout that they would need more than $8 billion in additional funding to build the infrastructure required to administer vaccines, such as setting up vaccination sites, recruiting workers, managing supply chains, community outreach, and modernizing data systems.

The Trump administration and congressional Republicans resisted providing that funding until late December, leaving states to split a pot of $340 million given to them earlier in the pandemic. That delay left states and chronically underfunded public health departments—which have been further strained by the pandemic—with few resources for what is a herculean task.

A “huge amount” of the problems we’re seeing now were caused by this lack of funding, according to Dr. Kass. “The lack of centralized communication and the lack of organization and investment on the infrastructure is what’s really been the core problem on delivery of vaccines.”

This lack of adequate information technology (IT) systems is a massive issue, according to Julie Swann, a vaccine distribution expert and head of the industrial and systems engineering department at North Carolina State University.

“Right now, you’ve got people all over the country scrambling to try to get access to vaccines. A lot of this information could be put into information technology systems that then tell someone, ‘Okay. It’s your turn to get vaccinated. We have some at a location near you. What time would you like an appointment?’” Swann told COURIER.

That sort of system does not yet exist at scale, and that void has forced some public health officials in states like Florida and Texas to resort to using the third-party website Eventbrite to schedule appointments, a less-than-ideal approach for a mass vaccination campaign.

Maricopa County, Arizona, the nation’s fourth most populous county, opened the kind of online portal Swann spoke of on Monday, but the site was quickly overwhelmed as people flooded the site to try and schedule appointments. New York City also set up a website, but the page has been criticized as being “burdensome and complex.”

“The @nycHealthy site has a multi-step verification process just to set up an account, and then a six-step process to set up an appointment,” city Comptroller Scott Stringer wrote in a tweet on Sunday. “Along the way, there are as many as 51 questions or fields, in addition to uploading images of your insurance card.”

New York City has since launched a phone line to schedule vaccination appointments, which Stringer praised.

The Weekly Guessing Game for Vaccine Doses

Another major issue in the rollout thus far has been that states haven’t always known how many vaccine doses to expect each week from the federal government.

“States don’t have much visibility to how much is coming two weeks from now, so they’re really responding on an almost real-time basis to get the vaccine allocated to specific locations,” Swann said. “That doesn’t give those specific locations a lot of advanced knowledge, either.”

This lack of information has hampered already difficult last-mile distribution—the process by which the vaccine gets from distribution centers into Americans’ arms—and states have struggled to distribute and administer the doses they’ve been sent.

“It seems hard for the states to plan distribution if they didn’t know how much they were going to get,” Dr. Kass added. “The federal government could have been a lot more organized at advanced planning with the states.”

States Make Their Own Mistakes, Too

State leaders bear their share of responsibility too.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, has drawn significant criticism for the state’s slow rollout. Cuomo bypassed county health departments and the vaccination plans they developed and instead assigned a major hospital in each region as the point agent in the distribution process. He also initially stuck to strict guidelines for who could be vaccinated and threatened to levy fines against hospitals who vaccinated anyone that wasn’t an eligible healthcare worker or resident of a long-term care facility—those who the CDC recommended be first in line for shots.

The governor’s threats and rigid rules helped lead to a massive backlog of vaccines, some of which expired and were ultimately discarded. Cuomo has since expanded who is eligible to receive vaccines to include 3 million more New Yorkers, including those 75 and older and some essential workers. As of Tuesday, New York, has only administered 41% of the doses it has received from the federal government.

In Texas, officials are relying on local pharmacies to be heavily involved in the vaccine effort, but providers have said the state has failed to give appropriate directions or information about when doses will arrive, how operations should be organized, and how to decide who to prioritize in the state’s larger pool of eligible vaccine recipients. The state’s lack of a centralized scheduling system has meant these pharmacies, as well as hospitals and other medical facilities, have had to develop their own scheduling systems and find a way to sync their patient data with the state’s immunization registry, a central hub which tracks Texans’ vaccination records and schedules of recommended immunizations. In some cases, providers had to input this data by hand, an enormous waste of time and resources.

Texas has also diverged from the CDC’s guidelines and has opted to prioritize those 65 and older ahead of essential workers, creating a disorganized free-for-all. Florida has done the same, and expanding the eligible pool of vaccine recipients there sparked massive lines and confusion as people began to compete for vaccines—a scene Dr. Kass likened to the Hunger Games films.

‘We Need to Have Larger Buckets of Patients’

These efforts to expand who is eligible for their first shots also address another reality: hesitancy among many healthcare workers and long-term care facility staff to get the vaccine, which in some cases, has contributed to the backlog of unused doses.

Given the issues with the rollout and the lack of federal investment, Dr. Kass—who supports the tiered rollout in order to ensure equity of vaccine distribution—said she understands why state officials are making adjustments.

“One of the major effects of the failure of the federal government—the last gift they’ve given us—has been the need to lean on definitively inequitable vaccination distribution plans in order to get people vaccinated because there isn’t enough support to do it in the way that we wanted to do ideally,” she said. “We’re realizing that at least until we get better infrastructure, it does seem like we need to have larger buckets of patients who can get vaccinated at the same time.”

On Monday, the Trump administration signaled it too supports expanding the pool of who can get a vaccine, urging states to provide shots to anyone 65 and older.

But making more people eligible for the vaccine at this early stage is not without its risks. Dr. Kass worries that once states expand the pool of possible recipients, there will be even more issues with scheduling, communication, and organization.

“We need to have very well-funded, reliable and secure communication strategies, scheduling strategies, follow-up strategies, adverse events tracking, and centralized registration, which we don’t have,” she said.

Swann also has her concerns. “One thing that worries me is that states may be expanding into populations and not have a sufficient supply to address the priority groups that were identified based on their risk,” she said. “For states that expand too fast, it could have the impact of worsening disparities.”

The Road to Vaccine Redemption

So how do we fix this rollout?

Dr. Kass believes that state and local leaders need to prioritize centralizing distribution by setting up large vaccination centers. “The states have to envision how to vaccinate their entire state, and they have to empower cities and local governments to do it in a really coordinated way,” she said. “In rural areas, you can do them at fairgrounds, whereas in urban areas you can do them at stadiums.”

Some jurisdictions are already doing just that. Los Angeles officials announced on Sunday that they would be converting Dodger Stadium, which has been the nation’s largest COVID-19 testing site, into a vaccination site beginning this Friday. On Monday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, announced that the Petco Park baseball stadium in San Diego and Sacramento’s CalExpo Fairgrounds would also be used as vaccination sites. Orange County officials also announced Monday that Disneyland theme park in Anaheim would be turned into a mass vaccination site.

State Farm Stadium in Maricopa County is also operating as a massive 24 hour, 7 day per week vaccination site. Both Arizona (24%) and California (28%) are among the bottom 10 states in percentage of doses administered thus far, a reality which Newsom has called “inexcusable.”

These efforts are exactly what is needed, according to Dr. Kass. “There’s nothing more important than that,” she said. “There are no football games that are more important than that, there are no baseball games that are more important than that…There are only a few specific places that can be used for this, and they should be.”

Such massive mobilization, of course, will require additional federal support. The good news is that $8 billion is on the way, due to the recently passed coronavirus relief bill. Now, those funds have to be used in the best way possible.

Dr. Peter Hotez, a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine, took to the pages of the Washington Post on Monday to call for additional mass vaccination sites and the resources needed to prop them up.

“That can happen only with extensive—and maybe costly—intervention from the federal government, both for logistics and financial support, to immunize on the order of 10,000 to 20,000 people per day in major metro areas,” Hotez wrote. “Setting up vaccination hubs won’t require only space; it also means hiring hundreds or thousands of vaccinators and support staff, and paying for security and parking attendants.”

Others have suggested removing barriers and making it easier for people to become vaccinators in order to address staffing shortages. Newsom also addressed this issue on Monday, announcing that California was expanding its pool of eligible vaccinators to include pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, dentists, paramedics, and others.

In Just Over One Week, a Brand New Biden Administration Takes Over

The other key factor in all of this, obviously, is that there will be a new presidential administration beginning on Jan. 20, when President-elect Joe Biden takes the reins of the federal government. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million shots in the first 100 days of his administration, a lofty goal that has been made even more difficult by the Trump administration’s lack of a national plan.

“My number one priority is getting the vaccine to people’s arms as we just did today as rapidly as we can, and we’re working on that program now,” Biden told reporters Monday after getting the second dose of his vaccine. “It’s going to be hard. It’s not going to be easy, but we can get it done.”

Biden, who has previously promised to “move heaven and earth to get us going in the right direction,” said he would unveil the final details of his national vaccination plan on Thursday.

CNN previously reported on Friday that his administration plans to release nearly every available dose of the coronavirus vaccine when he takes office, a break with the Trump administration’s initial policy of holding back half of its doses to ensure second shots are available to everyone. The Trump administration announced Tuesday it would revert course and release those doses.

Biden has also said he will use the Defense Production Act to compel companies to speed up vaccine production and has promised to send in mobile units to vaccinate people in hard-to-reach areas.

Dr. Kass is hopeful the Biden administration will dramatically overhaul the nation’s vaccination efforts and improve upon the chaos by investing in communities, practicing consistent messaging, and being transparent with data.

“I think the Biden administration is probably very much aligned with what I think needs to happen, which is that we need to have a centralized investment strategy and partnership strategy from the federal government to the states,” she added. That means “making sure that the states understand exactly what they’re getting and when they’re getting it and making sure they’re getting what they need.”

Will that get us to 100 million shots in 100 days?

“I don’t know. I’d like to think it’s feasible. I certainly think that we can’t say what isn’t feasible when we haven’t even tried,” Dr. Kass said. “We need 24 hour mass vaccination centers happening all over the country. How many vaccines can we do per day in a single mass vaccination center? I don’t know, because again, we can’t say what’s not possible if we haven’t even tried.”

Politics

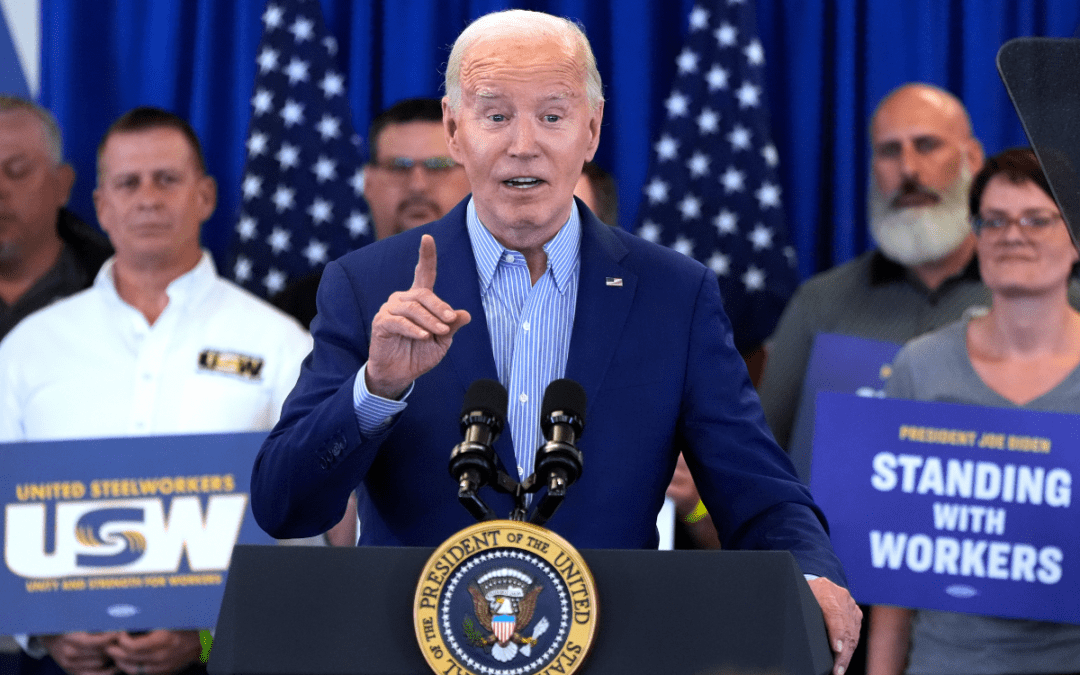

Biden announces tariffs on Chinese Steel while visiting United Steelworkers members

“I'm president because of you guys. I really am and I'm proud. As was mentioned earlier, I'm proud to be the most pro-union president in American...

Opinion: Is Reproductive Healthcare just a women’s issue?

In this op-ed, Pennsylvania resident Lynn Strauss discusses the Republican Party’s conflicting stance on reproductive healthcare policy and the...

2 top US gun parts makers agree to temporarily halt sales in Pennsylvania

Philadelphia filed suit against Polymer80 and JSD Supply last year, accusing the manufacturers of perpetuating gun violence by manufacturing ghost...

Local News

Conjoined twins from Berks County die at age 62

Conjoined twins Lori and George Schappell, who pursued separate careers, interests and relationships during lives that defied medical expectations,...

Railroad agrees to $600 million settlement for fiery Ohio derailment, residents fear it’s not enough

Norfolk Southern has agreed to pay $600 million in a class-action lawsuit settlement for a fiery train derailment in February 2023 in eastern Ohio,...