Image via Shutterstock

If you owe your bank overdraft fees, have delinquent loans, or owe other fees or charges—excluding credit card charges—they can seize your direct deposit payment and “offset” your debts.

Millions of Americans will begin receiving their $1,200 coronavirus relief payments from the U.S. government this week. But according to a report by The American Prospect, anyone who is in debt to their bank may not see a dime of that money.

When the federal government passed the CARES Act in March, they touted the one-time $1,200 coronavirus emergency relief checks that most Americans would receive. And indeed, payments have begun flowing into the bank accounts of people who previously authorized the IRS to deliver their tax refunds or social security payments through direct deposit. But Congress did not exempt these one-time payments from private debt collection, and the Treasury Department has thus far refused to use its regulatory authority to protect these payments.

This means that if you owe your bank overdraft fees, have delinquent loans, or owe other fees or charges—excluding credit card charges—your bank can seize your direct deposit payment as it’s routed through their accounts and “offset” your debts. Even if you think you’ve closed the bank account affiliated with your debts, should the IRS send your payment to that account, the bank can theoretically apply it to your old debts.

In other words, depending on how much you owe, you could be left with little to nothing of your $1,200 payment.

The Treasury Department more or less sanctioned this activity during a webinar with banking officials last week. In audio obtained by the Prospect, Ronda Kent, chief disbursing officer with the Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service, can be heard telling banks that “there’s nothing in the law that precludes” them from seizing payments from account holders who owe debts.

RELATED: Trump’s Just Put His Name on Your Coronavirus Stimulus Checks

One anonymous bank official who was on the call told the Prospect that they effectively viewed it as a green light for banks to take advantage of the coronavirus pandemic to collect prior debts. This could take away desperately needed aid from the nation’s most financially vulnerable people who may have been counting on that $1,200 to pay for rent and food.

The Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service did not respond to a request for comment from the Prospect.

“At a time when people are desperate to buy food, the idea that anybody would grab [the $1,200 payments], let alone the banks they trust with their money, is appalling,” Lauren Saunders, associate director with the National Consumer Law Center, told the Prospect.

Under the CARES Act, Congress exempted the payments from being seized by federal or state agencies and gave the Treasury Department the authority to exempt payments from private debt collection. The Treasury, however, has been reluctant to do so. And because the payments are defined as tax credits and not federal benefits (like social security or disability benefits), they are subject to “garnishment,” meaning a debt collector can take the debtor to court and seize the money.

It’s not just banks that could seize this money, either. “Payday lenders in many states have access to bank accounts and can seize that money as well,” Lisa Stifler, director of state policy at the Center for Responsible Lending, told the Prospect.

Other private debt collectors could also seek to take advantage of the payments and leave struggling Americans with nothing. “Creditors may view stimulus payments as an opportunity to seize money for amounts owed on outstanding court judgments. Millions of Americans have court judgments against them,” Saunders told MarketWatch.

The Treasury’s reluctance to issue an exemption for private debt collection comes despite pleas from lawmakers of both parties. Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Ron Wyden (D-OR), and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) wrote a letter to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin on April 3, calling on him to issue rules protecting the $1,200 payments from banks.

RELATED: 16.8 Million Americans Have Filed for Unemployment in Just Three Weeks

“Congress included this measure in order to help American families struggling to pay for food, medicine, and other basic necessities during the novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic and resulting economic crisis,” the lawmakers wrote. “To effectuate Congress’s intent, Treasury should ensure that CARES Act direct payments are treated the same way as other federal benefits and cannot be reduced to satisfy private debts.”

Sen. Josh Hawley, Republican of Missouri, later joined Brown in writing another letter making the same request. On Monday, 25 state attorneys general (23 Democrats and two Republicans) also demanded the Treasury issue regulations to protect CARES Act payments from garnishment.

The Prospect reached out to five major banks—Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citibank, and U.S. Bank—asking if they planned to use the payments to offset delinquent debts, and only one responded. JP Morgan Chase told the Prospect that while they would usually use incoming funds to offset a negative balance, they would instead return the money to the government.

“The U.S. Treasury can then determine the address to mail the full stimulus amount and ensure the former customer gets the full benefit,” spokeswoman Anne Pace said. She later clarified that this would only be the case for “charged-off accounts,” or debts that the bank has given up trying to collect on after several missed bank payments. This leaves the door open for the bank to use the payments to offset delinquent loans.

While the direct deposit distribution system of CARES Act payments is the fastest way to directly inject money into Americans’ pockets, it looks like it may also prevent many Americans from actually receiving the benefits of those payments.

Those Americans who do not have direct deposit information on file with the IRS don’t have to worry about banks seizing their payments—even if they owe debt—since these payments will be mailed via the postal service. But these individuals face another problem: They may not get their check until August or September, by which time, it may be too late for it to help them.

Politics

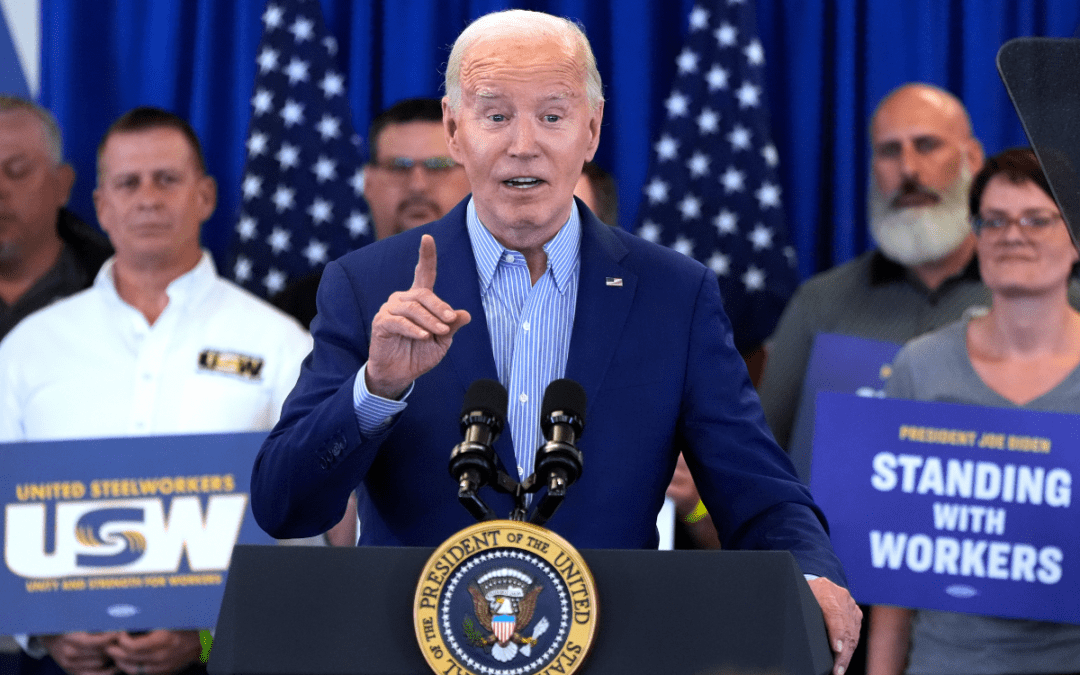

Biden announces tariffs on Chinese Steel while visiting United Steelworkers members

“I'm president because of you guys. I really am and I'm proud. As was mentioned earlier, I'm proud to be the most pro-union president in American...

Opinion: Is Reproductive Healthcare just a women’s issue?

In this op-ed, Pennsylvania resident Lynn Strauss discusses the Republican Party’s conflicting stance on reproductive healthcare policy and the...

2 top US gun parts makers agree to temporarily halt sales in Pennsylvania

Philadelphia filed suit against Polymer80 and JSD Supply last year, accusing the manufacturers of perpetuating gun violence by manufacturing ghost...

Local News

Conjoined twins from Berks County die at age 62

Conjoined twins Lori and George Schappell, who pursued separate careers, interests and relationships during lives that defied medical expectations,...

Railroad agrees to $600 million settlement for fiery Ohio derailment, residents fear it’s not enough

Norfolk Southern has agreed to pay $600 million in a class-action lawsuit settlement for a fiery train derailment in February 2023 in eastern Ohio,...