Sandwich caregivers often sacrifice financial security and are at higher risk of depression and mental health issues compared to non-caregivers.

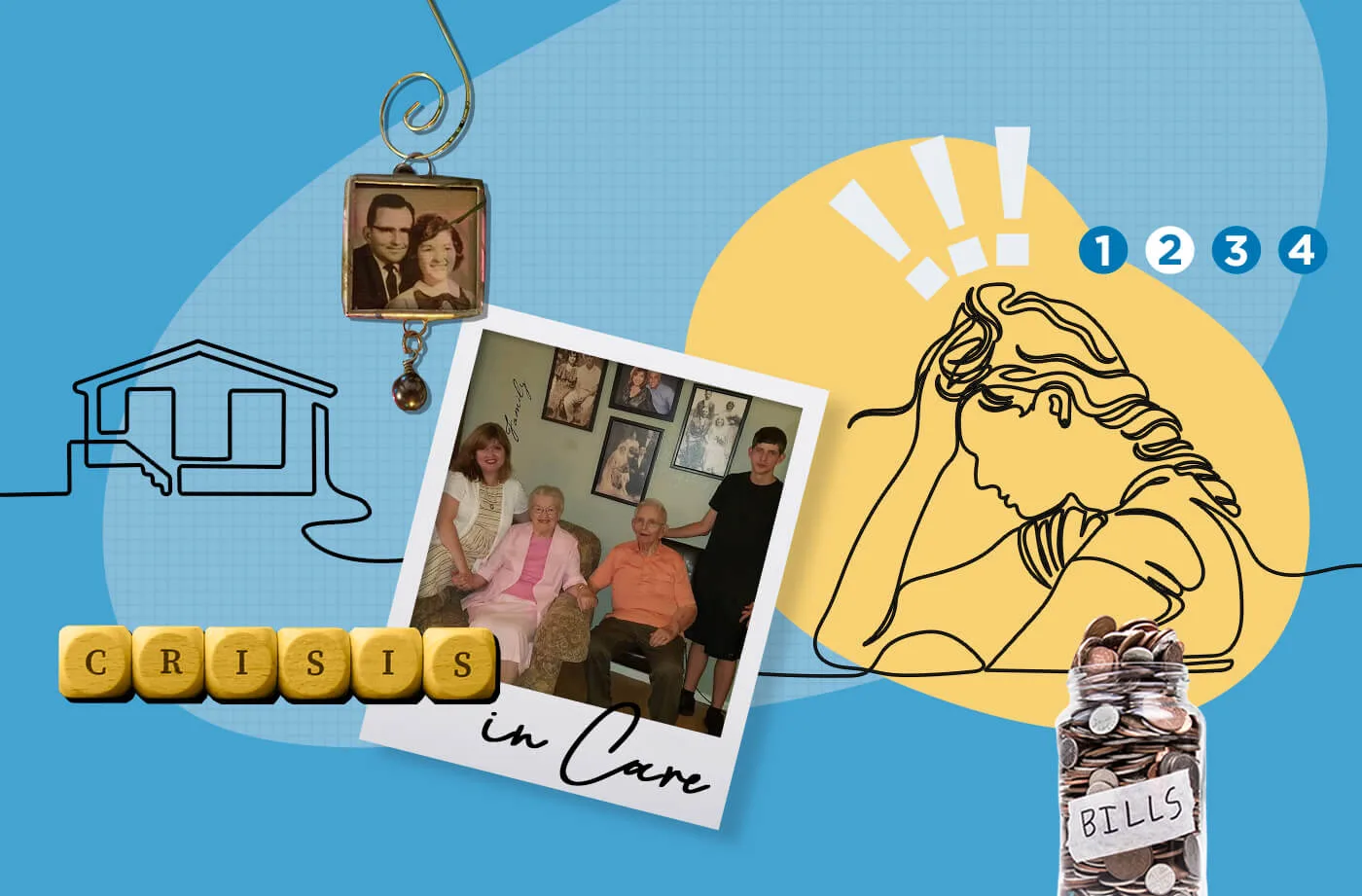

In Part One of our Crisis of Care series, we introduced you to Amanda Vingless, a Levittown resident who is raising her children and caring for her ailing father at the same time.

In a given week, Vingless has to juggle a full-time job with her children’s schoolwork, after-school activities, and sports schedules. But she must also navigate a whole other layer of responsibilities for her father. She ensures he has a filling breakfast every morning before she heads to work, manages his medication, schedules his doctors appointments, and does his laundry.

This constant balancing act takes a toll.

“There’s guilt with how much attention you’re giving this person or that person,” Vingless said. “Sometimes I feel pulled in different directions and some days I’ll go to bed and unwind from my day and think, ‘OK, did I not do enough for one person? Did I not do enough for another person, did I give this one enough attention?’”

Vingless is one of an estimated 11 million “sandwich generation” caregivers in the US. Like Vingless, these caregivers must somehow juggle an array of responsibilities that focus on not only their children but also their elderly parents. It’s often a struggle that is exacerbated by high costs and the lack of comprehensive child care and elder care systems in the United States.

In Part Two of our series, we take a deeper dive into the lives of sandwich caregivers: Who are they, what are their lives like, and what kinds of stressors do they face?

The Lives of Sandwich Caregivers

While all caregivers struggle to carve out time for themselves, this is particularly true for sandwich caregivers—61% of whom are women.

Sandwich caregivers with children at home spend, on average, 24 hours per week caring for their older parent, according to a 2019 report from Caring Across Generations and the National Alliance on Caregiving. These caregivers often help with transportation, housework, managing finances, filing insurance claims, and advocating with providers. Most also handle medical or nursing-related tasks.

Angie Roman is a married mother of four and grandmother of 10 who recently moved to Frackville, a small borough in Schuylkill County, with her husband to care for his aging mother. Roman might be new to the commonwealth, but she’s not new to caregiving. While living in Arizona, she spent more than two years as her father’s primary caregiver after he suffered a stroke. She brought him meals, managed his medication, and took him for night-time drives when he wanted to get out of the house.

After he died in 2016, Roman continued caring for her mother, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, for nearly four years. During all that time, Roman continued working and paid for full-time, private caregivers to help her mother during the day. She handled nights and weekends with support from her husband and teenage son.

It was never a question of whether Roman would step up to care for her parents, but the experience still took a financial toll. “Hiring the full-time caregiver pretty much took all of my after-tax, after-retirement savings, after the absolute essentials,” she said. “It cost us $30,000 a year for a full-time caregiver.”

Despite this strain, Roman, now 61, and her husband know they are lucky: They could afford to pay for the caregiver and had enough flexibility in their jobs to keep working.

‘A Huge, Huge Issue’: Sandwich Caregivers Face A Financial Strain

Many sandwich caregivers don’t have the kind of flexibility the Romans had. Too often, family caregivers lack access to paid leave, and are forced to leave their jobs, switch to part-time work, or otherwise reduce their hours in order to provide care. The consequences of sacrificing or delaying their careers can be severe.

“If a sandwich generation caregiver can’t secure adequate care for their child or for their loved one that they’re supporting at home or in their community, then it’s not just that day and that week’s finances that are impacted,” said Charlotte Dodge, senior policy and government affairs manager at Caring Across Generations. “They themselves are jeopardizing their own long-term financial well-being and retirement security.”

These caregivers are more likely to take on debt or spend down retirement savings in order to cover costs, and by leaving the workforce, they also forgo their ability to save for the future.

Even those who stay in the workforce might suffer from having to juggle roles. Studies have found that as many as 70% of working caregivers experience work problems, while nearly as many had to adjust their schedules as a result of caregiving. Others may keep working, but take worse jobs—which also has a negative impact.

“They may take lower-paying jobs and this really does result in lifetime consequences for earnings, for savings, and then their ability to retire comfortably,” said Heidi Donovan, a professor of nursing and medicine and the co-director of the National Rehabilitation Research & Training Center on Family Support at the University of Pittsburgh. “It’s a huge, huge issue for this group, and it’s something that we have to address at a national level.”

Caregivers don’t just lose income; they also spend more because of their caregiving duties. More than three-quarters of all family caregivers said they incurred out-of-pocket costs as a result of caregiving, according to a 2021 AARP survey. On average, these caregivers spend $7,242 per year on associated expenses and many cover rent or mortgage payments, medical costs, and home modifications. The toll is greatest on Black, Latino, and younger caregivers who have had less time working to accrue wealth.

In total, roughly half of caregivers say they have experienced financial setbacks, according to the AARP report.

The Impact Isn’t Just Financial

While the financial toll of being a sandwich caregiver is real, the psychological one might be even greater, especially when it comes to the role reversal that occurs when a person begins caring for their parents.

“My father is a very old-fashioned, independent man and didn’t want to be told what he could and couldn’t have, didn’t like the food restrictions and stuff like that, so we used to butt heads a lot,” Vingless said. “I wanted the best for him, but … he would say stuff like, ‘I lived a good life,’ and ‘I’m good, leave me alone.’ It was hurtful to watch him mentally try to give up on me.”

At times, her father also lashed out at her, which Vingless took personally at first. “I used to get so annoyed with it and so frustrated, like, ‘Why is he being like this to me? I’m taking care of him,’” she said. Eventually, with the help of an online caregiver program, Vingless realized that her father wasn’t angry at her, but the situation he was in. She just happened to be the closest person to vent at.

Becoming your parent’s parent, so to speak, can also be downright scary.

“It’s absolutely nerve-wracking,” Vingless said. “The dialysis place called me the other day because his blood pressure was low, and as soon as I see that number, my heart is already in my stomach, cause I’m thinking something went wrong.”

Her dad was OK, but false alarms aren’t uncommon for caregivers. They come with the territory.

Sandwich caregivers also feel stretched thin, according to Brenda Edelman, a licensed clinical social worker and the assistant director of Older Adult Services at Jewish Family and Children’s Service of Greater Philadelphia.

“Many times I’m talking to an adult child, they’ve got all this guilt, like, ‘I don’t know if I’m supposed to be my mother’s daughter or my husband’s wife or my children’s mother.’ They just feel very pulled and they have a lot of guilt,” Edelman said.

These sorts of feelings aren’t uncommon. Studies have shown sandwich caregivers report a high level of emotional stress, and are at higher risk of depression and mental health issues compared to non-caregivers.

Because they feel pulled in so many directions, many caregivers struggle to take care of themselves.

Tara Klinedinst is an occupational therapist and post-doctoral associate at the The National Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Family Support at the University of Pittsburgh. “I found that having no time for yourself was one of the strongest predictors of not being able to engage in meaningful activity, and not being able to engage in meaningful activity is associated with a whole host of poor mental and physical health outcomes,” she said, referencing a study she’s working on. “I think that is something that we really need to address with this cadre of caregivers because they really are stretched to the max.”

Caregiving Takes a Toll on Physical Health, Too

As Klinedinst noted, the stressful balancing act that is being a family caregiver can also lead to physical health issues. Among all caregivers over the age of 45, four in 10 report having two or more chronic diseases and may neglect their own personal health needs while providing care to others, according to a CDC brief.

“Caregivers are less likely to take care of their own health when they’re going through the circumstance; they’re more likely to experience increased levels of stress,” said Mike Wittke, vice president of research and advocacy at the National Alliance for Caregiving. “There was a report that Blue Cross and Blue Shield did recently that suggests that caregivers were more likely to engage in unhealthy coping mechanisms, like smoking or drinking, so it really has a high impact on their stress but also their physical health.”

But being a caregiver isn’t all bad, though. “It’s stressful and it’s exhausting but on my end of it, the greatest reward that I can say I get out of all this is that I get to do it for [my father],” Vingless said.

Studies have also found that caregiving builds self-confidence and problem-solving skills and can strengthen relationships. As for sandwich generation caregivers in particular, they have “greater emotional stability” and “higher resilience than older and younger caregivers,” Klinedinst said.

In order to improve their financial, physical, and mental health, however, caregivers need to find ways to utilize whatever resources are available to them. Those resources are confusing and often difficult to access, but they do exist. In Part Three, we dive into what help is available for sandwich caregivers.

Part One: Family Caregivers Struggle with a Broken System

Q&A: 11 Million People Are Raising Kids and Caring for Parents. Here’s One Therapist’s Advice for Them.

Part Three: A List of Resources Available for Pennsylvania Caregivers

Part Four: Pennsylvania and America Are in ‘Huge Trouble’ Unless We Help Families With Caregiving

Politics

How Project 2025 aims to ban abortion in Pennsylvania

Former president Donald Trump said abortion was a state’s rights issue recently, but conservative organizations, under the banner “Project 2025,”...

736,000 PA households could lose crucial help on their internet bills

Time is running out for the Affordable Connectivity Program, which provides low-cost high speed internet access for over 736,000 Pennsylvania...

What to know about Trump’s legal issues

Over the past year, former president Donald Trump has become the center of not one, not two, not three, but four criminal investigations, at both...

Local News

Conjoined twins from Berks County die at age 62

Conjoined twins Lori and George Schappell, who pursued separate careers, interests and relationships during lives that defied medical expectations,...

Railroad agrees to $600 million settlement for fiery Ohio derailment, residents fear it’s not enough

Norfolk Southern has agreed to pay $600 million in a class-action lawsuit settlement for a fiery train derailment in February 2023 in eastern Ohio,...