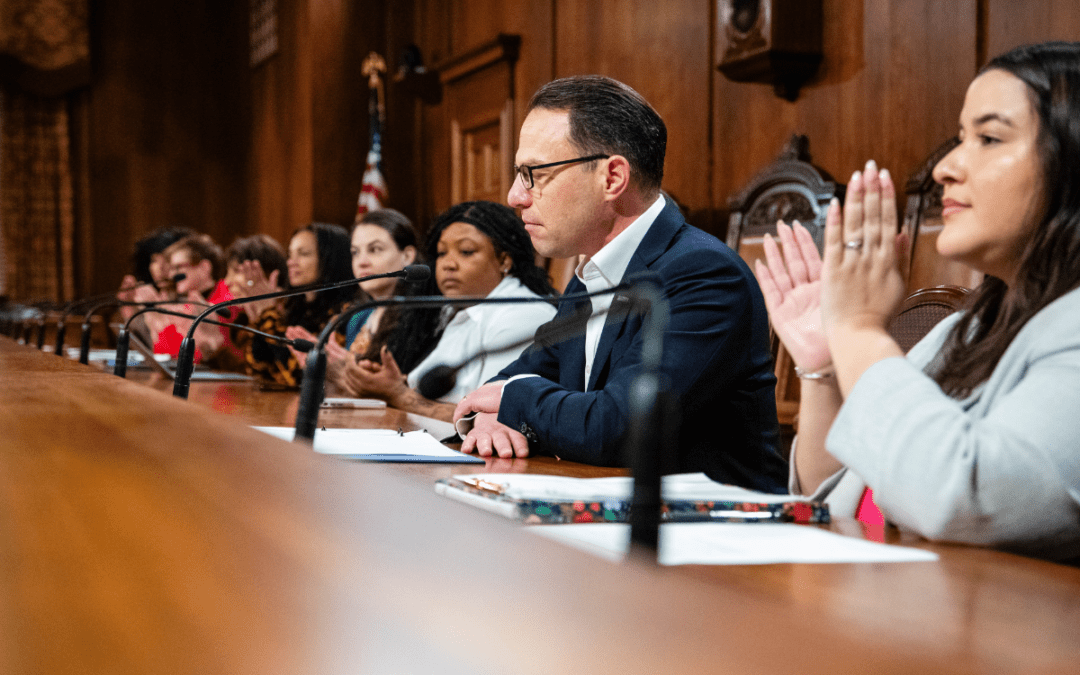

Tashia Bishop, right, sits next to a picture of her infant son as she testifies about her experience with pregnancy, motherhood, and loss during a state policy committee meeting.

Pennsylvania’s growing maternal and infant mortality crisis is blamed in part on maternity care deserts and stigmas around care. This is one woman’s story of pregnancy, motherhood, and loss.

Tashia Bishop never thought motherhood would begin with heartbreak.

The Delaware County resident suffered two miscarriages before giving birth to her first son prematurely. She was a recovering addict.

“I felt like the doctors and the hospital staff didn’t get to know me because of my drug history,” Bishop said. “I was put in a box and treated a certain way.”

Despite doing “everything right” during her recovery and pregnancy, Bishop said her repeated pleas about her son’s breathing troubles after his birth were dismissed as “over-anxious first-time mom” worries.

One night, she got her infant son ready for bed and read him stories before putting him to sleep.

“I didn’t know he would not wake up the next morning,” Bishop said.

Months after her son’s passing, she learned he’d suffered from a genetic lung disorder and viral pneumonia.

“Now that I have a second child, it’s hard for me to enjoy him 100% because I have a lot of fear that my second son will also pass away,” Bishop said.

A statewide crisis

Like many other states, Pennsylvania faces a maternal and infant mortality crisis.

“When mothers and babies are dying, it reflects not only a failure of our health care delivery but also a reflection of our broader social, economic, and policy environment,” said Dr. Aasta Mehta, director of Reproductive, Adolescent, and Child Health at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

In 2021, the commonwealth had a pregnancy-related mortality rate of 97 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the 2025 Pennsylvania Maternal Mortality Report. In other words, almost 130 women were documented to have died either during pregnancy, delivery, or up to one year after they gave birth.

“Black women in Pennsylvania die at more than double the rate of white women from pregnancy-related causes,” Mehta added.

Mental health conditions were the leading cause of pregnancy-related death, accounting for about 47% of cases, with overdose and substance use disorder being the primary causes.

For infant mortality, the commonwealth’s 2022 rate was 5.7 per 1,000 live births; Black babies die at more than twice the rate of white infants, most often due to prematurity and low birthweight.

Maternity care deserts

According to Mehta, one of the leading drivers of the maternal and infant mortality crisis is that many families, especially those living in rural counties, lack dependable and easy access to care.

A March of Dimes report found that more than 2 million women of childbearing age in Pennsylvania live in areas with little or no maternity care. About 12.4% must drive over 30 minutes to reach the nearest birthing hospital.

That number could rise as more hospitals face financial strain under Republicans’ “One Big Beautiful Bill.” The law cuts federal Medicaid funding by roughly $1 trillion over the next decade—money many rural hospitals rely on to stay open. It also imposes work requirements and forces recipients to reverify eligibility every six months instead of annually.

In Pennsylvania, about 3 million people —23% of the population—are covered by Medicaid, including more than 737,000 in rural counties. Medicaid pays for roughly 35% of births in the commonwealth. With the loss of funding and more patients becoming ineligible, hospitals are expected to take a financial hit, and some may be forced to close.

Southeastern Pennsylvania, for example, has already seen obstetric units close down because of low reimbursement rates and high liability costs, Mehta said.

“This combination makes it unsustainable for hospitals, especially community hospitals, to continue providing labor and delivery services,” Mehta said. “The result is that families are forced to travel further for care, putting both mothers and infants at risk and concentrating demand on fewer remaining hospitals.”

Mental health and substance use

After one failed attempt at getting clean, Bishop woke up one day knowing she needed to get better. She checked herself into rehab.

“I felt so good to be clean,” Bishop said. “Later, I became pregnant with my planned boy.”

Since Bishop was in recovery, she was participating in a methadone maintenance program which is used to treat opioid dependence.

“When I started my prenatal appointments I was really looking forward to meeting my OB doctors and my maternity team, but my experience wasn’t what I expected,” Bishop said. “I was drug tested at each visit and I knew my doctor didn’t approve of me being pregnant and on methadone even though it is a normal treatment for pregnant women who are in recovery. Methadone was helping to keep me clean during my pregnancy. I know that I was doing everything right.”

There is a stigma around pregnancy and substance use disorder, Mehta said, that needs to be addressed. Overdose is the leading contributor to pregnancy-related deaths in the state, yet maternal mental health and help with substance use disorder are not core parts of perinatal care.

In June, members of the PA Black Maternal Health Caucus introduced a package of bills called PA MOMNIBUS 2.0, which focus on reducing racial disparities in maternal and infant care, and addressing contributing factors like mental health and access to care. One bill in the package, HB 1192, would launch a pilot “mother’s treatment court” designed to help recovering mothers rebuild their lives with the support and resources they need. It’s currently stalled in a judiciary committee.

“There are too few psychiatrists, therapists, and substance use disorder providers trained in the care of pregnant and postpartum people, particularly outside of major cities,” Mehta said. “To reduce deaths, Pennsylvania must align regulations so that behavioral health can be delivered as part of routine perinatal care.”

Bishop said she is forever changed by her first experience with pregnancy and motherhood.

“I find it difficult to trust doctors and I worry about not being heard, not being believed,” Bishop said.

Support Our Cause

Thank you for taking the time to read our work. Before you go, we hope you'll consider supporting our values-driven journalism, which has always strived to make clear what's really at stake for Pennsylvanians and our future.

Since day one, our goal here at The Keystone has always been to empower people across the commonwealth with fact-based news and information. We believe that when people are armed with knowledge about what's happening in their local, state, and federal governments—including who is working on their behalf and who is actively trying to block efforts aimed at improving the daily lives of Pennsylvania families—they will be inspired to become civically engaged.

Doctors skeptical on Pa. governor candidate Stacy Garrity’s abortion pivot

Pennsylvania Treasurer Stacy Garrity, running against Gov. Josh Shapiro, campaigned with an anti-abortion governor on Sunday. Doctors aren’t buying...

Gov. Shapiro joins lawsuit against against Trump administration over defunding of Planned Parenthood

The suit centers on a provision of the recently-passed mega bill , which enacts many of President Donald Trump’s domestic policy priorities. Gov....

The scary reality of losing Medicaid and health care options for one Pennsylvania woman

In the wake of Trump’s ‘One Big Beautiful Bill,’ thousands of Pennsylvanians are waking up to a new reality: the loss of Medicaid coverage, and the...

Supreme Court limits nationwide injunctions, but fate of Trump birthright citizenship order unclear

WASHINGTON (AP) — A divided Supreme Court on Friday ruled that individual judges lack the authority to grant nationwide injunctions, but the...

Contraception is health care: Pennsylvania House passes bill to expand birth control access

With employer-provided insurance no longer required to cover birth control, many in Pennsylvania are struggling to pay for necessary medical care....