Andy Kochanowski shows how a plastic barrier keeps the cooling more efficient as it's pulled though the racks into the warmer areas. Paul Keuhnel, York Daily Record.

Back in May or June, David Naylor, chairman of the East Manchester Township board of supervisors, received a call from a woman who told him that she had received inquiries from a developer interested in buying her farm to build a data center.

“What’s a data center?” she asked Naylor.

Naylor wasn’t quite sure, so he did some research. It was a different kind of development for the rural northeastern York County township. The municipality is home to 8,400 people spread over 17 square miles, bordered on the east by the Susquehanna River, the bulk of it farmland. The township’s industrial zones are located in its westernmost tip and along a strip of land on the west bank of the river, between the York Haven hydroelectric dam and the Brunner Island power plant downstream.

A “Rezoning Public Hearing” sign is posted in East Manchester Township, where officials and residents have grappled with potential data center developments and associated zoning changes.

Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record

The farm in question is adjacent to the Royal Manchester Golf Links, an area not zoned for industrial use. The story circulating in the township was that developers were looking to build a massive data center on the grounds of the golf course. The township had not received any plans for such a facility.

As the weeks passed, and as rumors and speculation abounded, the township supervisors met to discuss the matter, scheduling a public hearing for Oct. 14 at the township office. So many residents turned out for the meeting, the crowd spilled into the parking lot. The supervisors decided to postpone the hearing so they could find a larger hall to accommodate the crowd, moving it to the fire hall the following week.

The township manager said she had never seen that kind of turnout. Neither had Naylor. “I’ve been a supervisor for a while and this topic got a lot of interest from the community,” he said.

Residents attend a public meeting in East Manchester Township, York County, where officials decided to remove a golf course from consideration for a data center rezoning plan. Lena Tzivekis, York County News

During the four-hour hearing, residents asked a lot of questions about the impact such a data center would have on their township and how the supervisors intended to handle it.

The supervisors responded by posting 11 pages of questions and answers on the township website as it grappled with this brave new world, an evolution, culturally and economically, on par with the industrial revolution of more than a century ago.

Naylor said the township is still working on its zoning regulations to limit where a data center can be built. The township has researched how other jurisdictions have handled the issue and how to mitigate any detrimental impact such a potentially huge development would have on its rural nature.

Andy Kochanowski shows how a plastic barrier keeps the cooling more efficient as it’s pulled though the racks into the warmer areas. Paul Keuhnel, York Daily Record.

Speaking to the hundreds of residents who crowded into the fire hall for the public hearing, Naylor said, “I’m confident we can’t please everyone, and some uncomfortable decisions will still need to be made by us up here, for us to protect our township and prevent somebody from coming and putting a data center anywhere they want. Our intent is to make the standards high enough that if and when anyone comes in, they’re built where we want it and how we want it.”

Later, Naylor said, “We’re trying to get ahead of it.” That’s easier said than done. Hardly a week goes by without rumors of a massive data center being proposed somewhere in York County.

“The ball is rolling fast downhill, and we have to get ahead of it or we’re going to be run over by it,” Naylor said. “We don’t want to be caught behind the eight-ball.”

Briarwood Golf Course in West Manchester Township was the subject of a public hearing about data centers in October 2025. Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record

‘Cannot be justified on grounds of job creation’

Data centers are sprouting up like toadstools after a rainstorm.

As of March, the United States had over 5,400 data centers, more than 10 times as many as the next country on the worldwide list, Germany. From 2021 to 2024, the number of data centers in the United States nearly doubled. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, the demand is expected to increase by 9 percent annually through 2030.

With that growth comes the massive demand for electricity to power data centers. In 2024, according to a report by the Brookings Institute, data centers consumed 4.4 percent of the electricity generated in the country. With the growth of artificial intelligence and its steep power demands, the percentage is projected to grow to as much as 21 percent by 2030. For instance, an Amazon data center in Luzerne County consumes about as much electricity as Pittsburgh, according to testimony before the state Public Utility Commission.

The reason for that growth is obvious. Every time you check your bank balance, pay a bill online, buy something with a credit card, teleconference with coworkers, post a picture of what you had for dinner on Facebook and just about anything else, you are accessing a data center, whether it’s computing a transaction or storing a photo of your cat in the cloud. And the growth in artificial intelligence requires massive amounts of computing power and data storage.

Pennsylvania has been working to attract some of the hundreds of billions of dollars that are expected to be invested in data centers in the coming years. The 2021 Computer Data Center Sales and Use Tax Exemption Program exempts data center equipment from state sales and use taxes.

Earlier this year, the state attracted $90 billion in investments to build data centers and improve electrical generation. The investments include construction of a $5 billion data center in Peach Bottom Township, near the York 2 Energy Center gas-fired power plant, and a 20-year commitment from Google to upgrade the Safe Harbor and Holtwood hydroelectric plants on the Susquehanna.

York County is also entertaining proposals to build data centers in Fairview, Windsor and West Manchester townships, projects that are awaiting zoning approval to move forward. Like East Manchester Township, other municipalities are grappling with zoning restrictions even before receiving proposals for data centers.

Other municipalities and cities have dealt with land use questions differently. For instance, a proposed 1 million square foot data center in Lancaster is being housed in repurposed industrial buildings, the hub being the former R.R. Donnelley printing plant near Harrisburg Pike. The $6 billion project did not require any land-use review by the city since “a data center use has been deemed consistent with the zoning district,” according to the city’s website.

Residents have expressed skepticism about the developments. While the huge projects would bolster local tax bases, people are concerned that the increased demand for electricity and the cost of upgrading transmission lines would be passed on to consumers.

Data centers also consume massive amounts of water, used to cool the processors, and there is public concern that it would result in higher costs for water. York Water Co. is not concerned about that, said CEO J.T. Hand, who believes such facilities “could become powerful economic engines” for the state and region. “We are ready to meet the needs of any data center that comes to our territory,” he said. “We have the capacity.” He also said the water company has tariffs in place that would prevent any costs related to the centers to be passed on to residential or business consumers.

Residents are also concerned about noise from the centers’ cooling systems, a constant hum, and having such nuisances near residential areas, Naylor said. In short, residents don’t want data centers in their backyards, a sentiment echoed by, of all people, Microsoft’s principal corporate counsel. Speaking at a webinar titled “Data centers: Construction, contracts and debt,” the software giant’s lawyer, Lyndi Stone, said, “Where data centers used to be built more away from communities, neighborhoods, and more urban areas, then you have neighbors that are near you, and nobody really wants a data center in their backyard. I don’t want a data center in my backyard.”

Andy Kochanowski’s data center supports individual companies seeking extra security and redundant cooling and power supplies. Paul Kuenhel, York Daily Record

The industry, though, touts its contributions to the economy. Lucas Fykes, director of energy policy for the Data Center Coalition, which represents data center operators, told the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, “The importance of data centers is difficult to overstate, in part because nearly every sector of the modern American economy relies on cloud computing – a service facilitated by data centers – in some way.”

A study commissioned by the industry group found that in 2023, data centers supported 4.7 million American jobs, including 603,900 direct jobs, an increase of 51 percent since 2017. Data centers contributed $727 billion to the gross domestic product in 2023. Every data center job supports six other jobs, and the industry was responsible for $162.7 billion in federal, state and local taxes.

However, economists who have crunched the numbers cast some doubt on those claims, noting that jobs created by developing massive data centers are often more than offset by job losses caused by the integration of artificial intelligence into other industries and businesses. For instance, in October, Amazon announced it was laying off 14,000 members of its corporate workforce. Its senior vice president of “People Experience and Technology,” Beth Galetti, wrote in a blog post, “This generation of AI is the most transformative technology we’ve seen since the Internet, and it’s enabling companies to innovate much faster than ever before (in existing market segments and altogether new ones). We’re convinced that we need to be organized more leanly.”

Michael Hicks, a distinguished economics professor and director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University, wrote in an analysis of data from Texas, published Nov. 10 that “there is a gross increase in data center jobs in a county, when the data center opens. But these results conclude that these job cuts are offset by job losses in other sectors. In other words, though there are gross job flow changes, there is no discernable net change in jobs associated with the data centers in Texas.”

Hicks concluded, “Given their large capital purchases, most state and local governments should experience growth in sales and use as well as property tax revenue from these activities. Those revenues could be deployed to improve local amenities, offset other revenues or compensate households experiencing negative externalities.

“What is very clear from the results of these causal estimates of employment effects is that fiscal incentives for data centers cannot be justified on the grounds of job creation. State and local governments should suspend existing tax incentives and defer any future incentive decisions until more analysis has been completed.”

York County naturally attracts data center developers

Kevin Schreiber, president and CEO of the York County Economic Alliance, said, “York County is an attractive location because we have a concentration of power generation capacity and because of the proximity of telecommunications infrastructure that moves internet traffic along the eastern seaboard. Land prices in our area are significantly cheaper than in areas directly around New York City, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia.”

He also said that data centers can generate tax revenue for local government and school districts, but he cautioned that such developments should conform with the county’s comprehensive plans. YCEA supports using “brownfield” sites and vacant industrial land to site data centers, balancing economic growth while preserving the county’s agricultural heritage.

The alliance has been approached by a number of data center developers and has acted as an information broker, providing access to a mapping app that identifies vacant and underutilized industrial sites that may be available for such large-scale development.

“These growth zones are important because in a growing county with limited developable industrial parcels, greater weight should be given to ensure evaluation of the highest and best use of that land, to include manufacturing with high-wage, family-sustaining jobs,” Schreiber said.

For all of the talk of growth, investment analysts have expressed concern that the boom in data center development is overestimated, that some of these massive projects may remain idle, leaving residents shouldering the costs of infrastructure improvements made to accommodate the centers’ demands, something called “stranded investments,” according to the state consumer advocate’s office.

Acting state Consumer Advocate Darryl Lawrence testified before the state Public Utility Commission, “Any stranded investments from large load customers paid by ratepayers hinders economic development by raising the cost to businesses and reducing spending by residents. The impact of a clothing store that reduces its hours for its staff because families tighten their clothing budgets is not visible to the public. Its economic impact adds up across families and is just as important as the evident economic activity of building a data center.”

East Manchester Township Chairman Naylor said he is researching all these questions. “We tried to answer all of the questions,” he said. “I’m glad I’m retired. It’s a full-time job.”

Three Mile Island is now called the Christopher M. Crane Clean Energy Center. Officials from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission briefed reporters on the process of restarting the plant’s unit 1 reactor, which was closed down in September 2019. Owner Constellation has entered an agreement with Microsoft to sell electricity generated by the plant to power data centers. Mike Argento, York Daily Record

Power hungry

In April, the PA Public Utility Commission held a hearing with the goal of figuring out a regulatory framework that would accommodate the huge demand for power while considering the possible cost to consumers. The commission heard from data center developers, utility executives and consumers. After the hearing, even Walmart piped in.

The goal was to find a balance, something that is especially important since, in the words of Allison Kaster, director of the commission’s Bureau of Investigation and Enforcement, “Pennsylvania is an attractive location for data center operators due to low-cost rural land and property taxes, as well as the currently abundant supply of natural gas and excess electricity.”

The industry understands that it needs to address the concerns of consumers. Michael Fradette, a principal of energy services for Amazon Data Services, told the PUC, “We recognize the need for a balanced approach that supports technology, technological advancement, sustainable energy practices and fair cost allocation.”

And that has to happen as demand is expected to spike in the coming years. The PJM Interconnection, which operates the electrical transmission service in the mid-Atlantic region, estimates that demand will grow by 17 percent by 2035.

“This potential demand growth is unlike anything we have ever dealt with before,” Richard Webster, PECO Energy’s vice president for regulatory policy and strategy, testified before the PUC.

The Brunner Island power plant in York County is a large producer of power. Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record

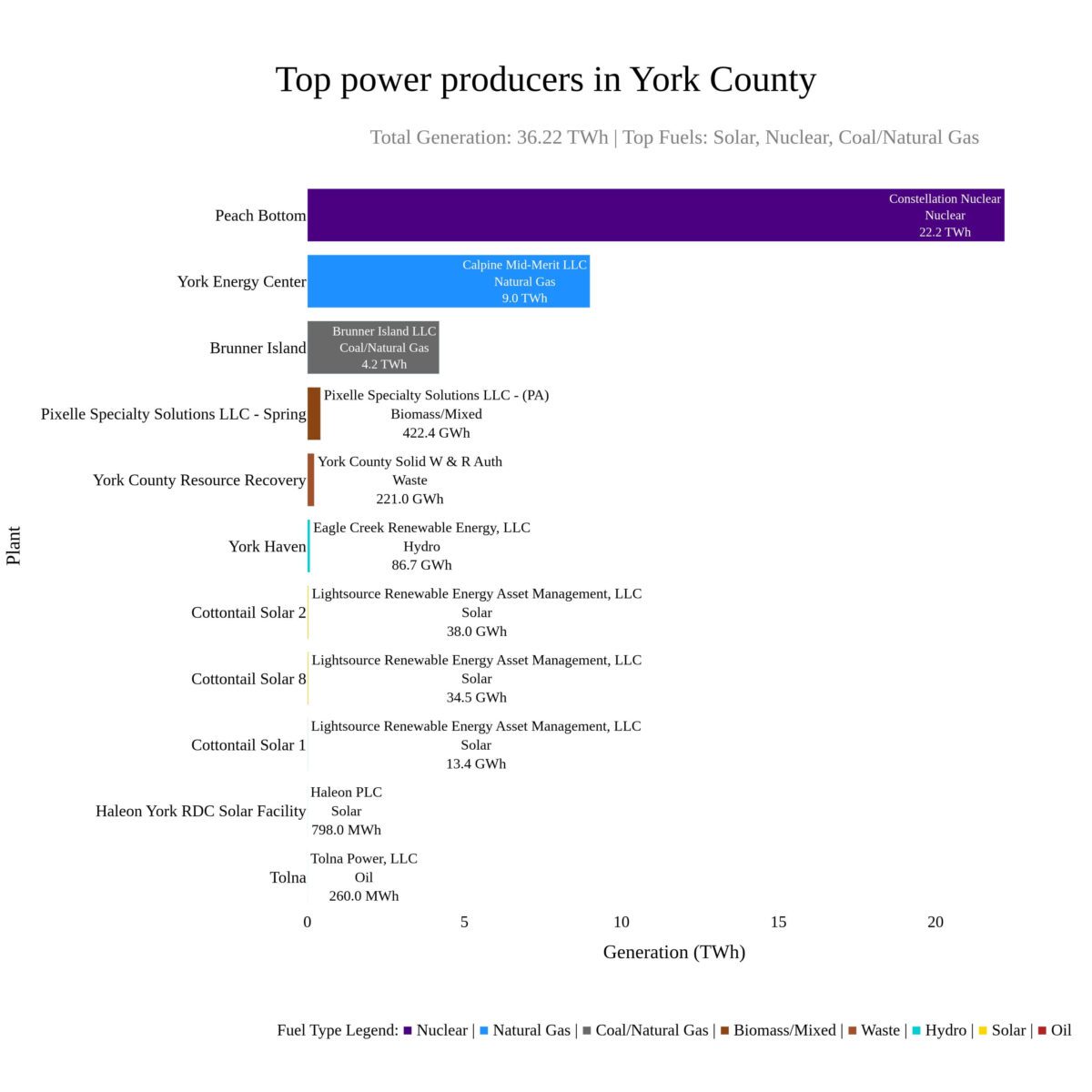

York County No. 1 power producer in PA

York County contributes a massive amount of electricity to the grid, ranking No. 1 among Pennsylvania’s 67 counties and No. 3 among all counties in the country, according to GridInfo.com, which tracks electrical generation in the United States. The largest generating plants include the Peach Bottom nuclear power plant, York Energy Center’s gas-fired plant, Brunner Island in East Manchester Township, the York County Solid Waste Authority’s trash incinerator and the York Haven hydroelectric plant. (Technically, the Holtwood and Safe Harbor hydroelectric plants on the Susquehanna are in Lancaster County because the border between the two counties is the river’s west bank.) Additionally, Constellation, owner of Three Mile Island’s decommissioned unit 1 reactor, is working on reopening that plant in two years to provide electricity exclusively to Microsoft’s data centers.

Data from GridInfo.com show the top electricity producers in York County. According to the site, York County is the No. 1 power producer in Pennsylvania and No. 3 nationally. Data Source: Gridinfo.com

During the hearing, PUC Chairman Stephen DeFrank said the commission’s goal is to develop regulations that accommodate data center demand while protecting consumers from picking up the tab for projects that fizzle out.

On Nov. 6, the PUC, by a 3-2 vote, issued a tentative order proposing regulations, called a tariff, “to guide how large electric customers connect to the grid and share costs responsibly,” according to a PUC press release.

DeFrank said, “Pennsylvania has a real opportunity here – if we get it right. Today’s tentative order is about welcoming investment and jobs while making sure existing customers aren’t stuck with the bill.”

Gov. Josh Shapiro, while touting a $20 billion investment from Amazon Web Services to build data centers in Bucks and Lycoming counties, believes that it can be accomplished. He has said that the state is “all in” when it comes to developing data centers, saying it would create jobs and spur economic development.

Peach Bottom Atomic Power Station is located in southern York County. The power planet houses two nuclear reactors. It is the largest power producer in York County. Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record

Shapiro supports measures that would require data center operators to generate their own power while aiming at converting coal-fired plants to natural gas. Shapiro, at a conference on artificial intelligence in September, said the state can power data centers “while still being able to deliver reliable, affordable, plentiful energy for small businesses and our homes.”

The state House is considering legislation that would codify regulations governing data centers. Beaver County Democratic Rep. Robert Matzie’s bill would direct the PUC to establish regulations on data centers, mandating, among other things, that a public utility cannot charge ratepayers costs directly attributed to a data center.

State Rep. Joe D’Orsie, a Manchester Republican whose district may be the site of a large data center and who serves on the House Communications and Technology Committee, favors a mandate to require data center operators to generate their own power as a means of protecting ratepayers from rate increases and a scarcity of power. By the same token, he said he believes data centers can provide jobs and tax revenue and that the state’s regulatory and tax policies should make it attractive to such development.

“I would rather Pennsylvania be a cutting-edge technological hub than our surrounding states, or even China,” he said. “These factors should be considered when we’re discussing data centers.”

But, he admits, he is grappling with developing a regulatory framework for data centers.

“The answer to this question isn’t easy, as this is an emerging technology, and everyone is trying to wrap their arms around it,” he said. “There is a lot of uncertainty in the AI space, but a knee-jerk reaction to overregulate from the state’s perspective would be a mistake, in my opinion.”

These are decisions that could have ramifications for decades.

In testimony before the state Senate Democratic Policy Committee, DeFrank, who generally supports Matzie’s bill, said, “These are extraordinary times in the energy sector. The decisions we make in the next five to seven years will impact us for the next 70 years.”

Andy Kochanowski shows how a “mantrap” works in his Alerify data center. The double access adds security to the entry. Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record

Inside a small data center

Not all data centers are behemoths five times the size of a Walmart Supercenter covering acres of what used to be prime farmland.

Tucked away in an office building in a commercial area in suburban Harrisburg, sharing space with the state Department of Human Service’s Bureau of Hearings and Appeals, is a company called Alerify.

It’s what you could call a mom-and-pop data center. You enter the 2,500-square-foot center through something called a “man trap,” a steel security cage inside the door off the office building’s hallway. “A security measure,” proprietor Andy Kochanowski said.

Kochanowski had spent 30 years in the tech industry, working for Comcast and Windstream, among others, and a couple of years ago decided to start his own business, applying what he had learned in the industry. “For me, it was more about pursuing a career path I’ve never done before,” he said. “After being in the military and the corporate world, I thought it’d be nice to own my own business.”

The business serves as “a storage unit” for businesses, Kochanowski said. Instead of a business having a rack of servers and associated gear in a closet, it can rent space from Alerify. The company has four employees. It’s similar to a mega data center, Kochanowski said, except “it’s not a million square feet like some of the hyper-scalers.” Electricity is his largest expense, but that is offset by solar panels that provide 30 percent of his power.

Outside, Kochanowski shows how noisy the operation is. Its air conditioning fans emit a low roar. “Imagine multiplying that by hundreds,” he said, comparing it to the noise produced by a huge data center.

Andy Kochanowski shows how a “mantrap” works in his Alerify data center. The double access adds security to the entry. Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record

He is concerned that the mega-data centers will be able to poach his customers since the large companies have the advantage of scale and are receiving tax breaks.

It’s a complicated situation, and whether it’s how communities can accommodate huge data centers or how they can meet their energy demands while protecting consumers, it’s still in flux.

One thing is certain, Kochanowski said.

“Some retooling needs to be done.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: From farm fields to server farms, York County grapples with potential data center invasion

Reporting by Mike Argento, York Daily Record / York Daily Record

USA TODAY Network via Reuters Connect

Related: ‘Will solar panels replace farms?’ Answering your questions about clean energy in PA

Shapiro hints at permit denial to stop Pa. ICE detention centers

Permitting and infrastructure concerns may trip up immigration detention centers despite DHS secretly purchasing two empty, rural Pennsylvania...

Pa. small businesses cheer U.S. Supreme Court tariffs decision, but still face uncertainty

by Whitney Downard, Pennsylvania Capital-Star February 23, 2026 Thousands of small businesses across the commonwealth paid billions of dollars under...

ACLU calls for ‘full, transparent’ investigation of Quakertown ICE protest

ACLU of Pennsylvania is calling for a "full and transparent investigation" of an off-campus ICE walkout that resulted in physical confrontations...

Quakertown protest against ICE turns violent, arrests made

Quakertown School District officials canceled a planned student-led walkout Friday at its high school over Immigrations Customs Enforcement...

Bucks County DA launches investigation into Quakertown PD protest response

The Bucks County District Attorney's Office is opening an independent investigation into how police handled the Quakertown student walkout, a...