This is an undated image of the Hotel Pope at East 13th and French streets in Erie. Photo provided by Hagen History Center via Reuters Connect

Segregation was the norm and the Ku Klux Klan was at the peak of its power when Jessie Pope advocated for racial equality.

An early president of the Erie branch NAACP, Pope spoke out against prejudice, segregation and white supremacy at public gatherings, club and political meetings, and before city leaders from 1918 until her death in 1942.

Pope also was a businesswoman. She owned and operated the Hotel Pope, the longtime cultural hub of Erie’s Black community.

The ‘hydra-headed monster’

At a Labor Day picnic at Presque Isle in 1918, Pope, then known as Jessie Reid, spoke about racial prejudice in Erie, citing housing discrimination, segregation at public venues and injustice at the city’s munitions plants, where new immigrants “foreign by birth and alien by speech” were hired before qualified Blacks.

The “hydra-headed monster” could only be defeated if everyone worked together, Pope said.

“The only way to kill it is for every man and woman without a yellow streak, both in public and in press, to decry against this hidden wolf which is gnawing at the vitals of American democracy.”

Just 29 years old, Pope already was an acclaimed speaker. She became the public voice of the first Erie branch of the NAACP when it was chartered in December 1919.

Pre-empting the Ku Klux Klan

In 1921, Pope led a delegation that alerted city officials to the Ku Klux Klan organizing in the city. Pope was well known to local politicians. She was an active member of both the Negro Division of the Erie County Republican Party and Erie County Negro Democratic Society.

Local authorities found no evidence of the Klan, Mayor Miles Kitts wrote in an open letter to Pope on Oct. 3, 1921.

“Nor will we tolerate for a moment its organization or operation within the city of Erie,” Kitts assured.

Weeks later, an admitted Klan organizer was ordered to cease operations in the city and to vacate his “Keystone Patriotic Society” premises.

‘Regardless of race, creed or color’

When the Erie County Prison Board proposed segregating female inmates by race in May 1924, Pope, by then president of the local NAACP, led the opposition.

“To our minds, prisoners are prisoners regardless of race, creed or color,” NAACP leaders wrote in a letter to the prison board. Segregation at the prison, they said, “would be an incentive to a city-wide discrimination and segregation, especially in public places.”

Blacks deserve equal rights in the democracy they fought for “in each and every war from the Revolutionary to the World War, even to the extent of giving their all,” the NAACP wrote, and any action fostering “dissatisfaction between the races” must be rejected.

‘Pleading for justice’

Pope addressed Erie civic groups through the 1930s, “pleading for justice” for her race, the Erie Times-News wrote.

The text of Pope’s talks was not always reported. Reaction to the talks sometimes was, as on Sept. 2, 1923, when Pope addressed the Zonta Club at the Lawrence Hotel.

The talk was well received, the newspaper reported, by Zontians who were “deeply interested” in the injustices Pope detailed.

‘Herculean efforts of a people’

In February 1940, Pope responded to an Erie Times-News columnist who speculated that Blacks may have been better off in the old South.

Jay James wrote that most Blacks were “happy, contented and well cared for” while enslaved, and at present were “mostly miserably poor” in “vice-ridden, disease spreading, squalid districts” of the North.

In a letter to the editor, Pope replied that James saw freedom as “just a fallacy and a dream,” and ignored the accomplishments of her race.

“Would you cast out of American history so lightly the herculean efforts of a people who, in the face of adversity and discrimination in seventy-seven years of freedom, have forged ahead in literature, arts, science and music,” Pope wrote, citing Erie composer Harry T. Burleigh, Marian Anderson, George Washington Carver and others.

If some Blacks lived in ghettos of vice and disease, Pope wrote, “that may easily be removed by the landowners renting suitable and equal homes to all races.”

The Pope Hotel

Jessie Pope and husband William Pope opened the Hotel Pope, commonly known as the Pope Hotel, at 1318 French St., on June 14, 1924. Jessie Pope operated the business.

The hotel’s nightclub was the the city’s leading venue for “sepia” performers, including both local talent and acts from New York’s Apollo Theater and Kit Kat Club.

Pope’s son, Ernest Wright, took over management of the hotel in 1933 and ownership in 1942, when Jessie Pope died at age 53.

Under his management, the hotel hosted Pearl Bailey, Duke Ellington and other Black headliners who performed in Erie but weren’t welcome at other hotels, according to A Shared Heritage, a community history project on Erie’s African-Americans.

The Pope Hotel and night club were open to all.

“… The Pope Hotel was popular with Black patrons as well as white customers drawn by the top-notch entertainment,” Jeff Sherry wrote in a Hagen History Center blog.

The building and business declined over time. The hotel was demolished in 1978.

USA TODAY Network via Reuters Connect

Related: Celebrating Philadelphia’s place in Black music history through 13 essential artists

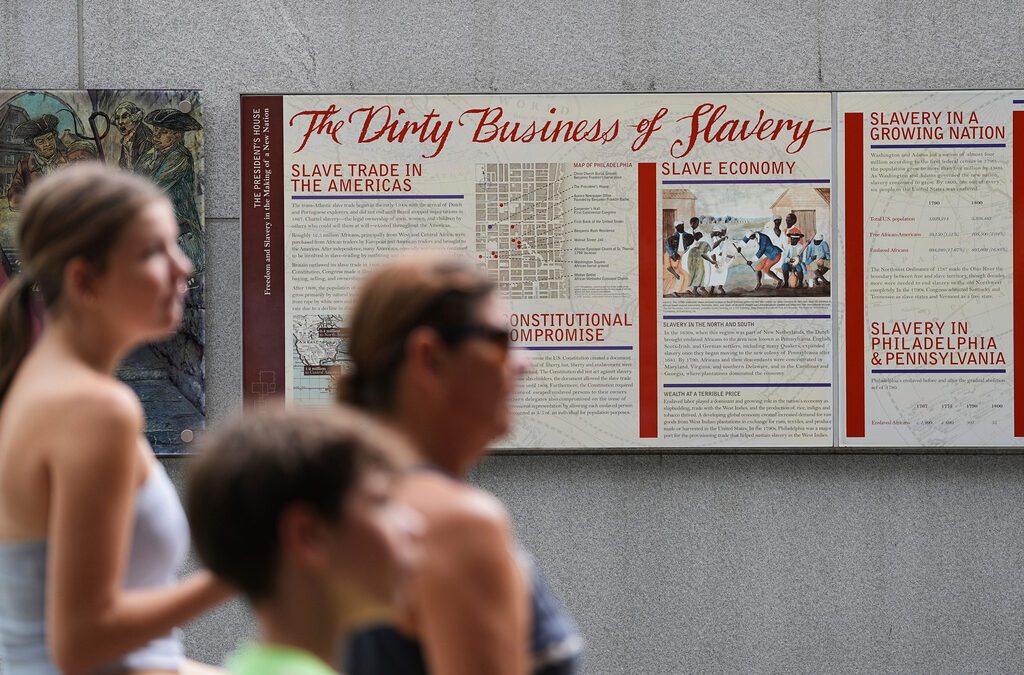

Judge calls Justice Department’s statements on Philadelphia slavery exhibit display ‘dangerous’ and ‘horrifying’

A federal judge warned Justice Department lawyers on Friday that they were making “dangerous” and “horrifying” statements when they said the Trump...

10 key stops on the Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania

As the Trump administration aims to whitewash certain aspects of US history, it’s an important time to reflect on the significant achievements of...

Everything to know about Groundhog Day 2026 in Punxsutawney

Celebrate Groundhog Day 2026—and its ancient origins—at the popular Western Pa. event where you can catch a glimpse of the world’s most famous...

So you’re freezing? Forgive the Pa. explorer who invented wind chill

The thermometer doesn't always tell us how cold it feels outside. An Erie man came up with a formula that does. Wind chill, or how cold it actually...

How soap led police to killers of Erie industrialist 81 years ago

Dubbed the "Hilltop Murder," the 1945 killing of Joseph B. Campbell at his Millcreek home was "one of Erie County's most atrocious crimes,"...