Kelley Bashew (Courtesy Kelley Bashew)

Kelley Bashew decided to look for her birth family when she turned 50. She found herself and became an advocate for Indigenous people.

MONTGOMERY COUNTY — She was born Rose Ann Owen on March 6, 1963 in Sisseton, South Dakota, on the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation. The nice Irish-Italian couple from Glenside, Montgomery County, who adopted her when she was 3 months old changed her name to Kelley Petrilli.

She was the oldest of six Petrilli children, but the only one who was adopted and an American Indian. The Petrillis loved all of their children equally and sent them to Catholic school.

But Kelley Petrilli, now Kelley Bashew, looked different from her Irish-Italian siblings. She was taller and had a darker complexion. She always felt different. When she turned 50, she decided it was time to find her birth parents.

“Even though you know you’re loved, and you had a good life, there is a big pull, I think a lot of adoptees have it, Native or non-Native, you know you just have that pull of not being connected,” she said. “And you know there’s another family out there.”

Finding her birth family and learning more about her heritage led Bashew to find a new sense of purpose. As a board member of the Coalition of Natives and Allies, she is working to educate others about Indigenous history, and improve the lives of Indigenous people living in the commonwealth.

Connecting With Her Birth Family

In 2013, Bashew called Pierre, South Dakota, to get her birth certificate. She learned her parents’ names were Hiram and Lillian Owen, and she learned that she had been born in Sisseton. She told her adoptive family she wanted to meet her biological parents and they gave their blessings without hesitation.

Bashew found a woman online who was knowledgeable about South Dakota adoptions, and she connected her with Dave Bova, who is from Sisseton. He found the Owens. The couple and their eight children were eager to have a conference phone call with Bashew. She learned she is the second youngest of nine — eight girls and one boy.

“The first time we spoke, it was like everything fell into place,” Bashew said.

She visited Sisseton two weeks after that call. She said she felt excited, not nervous, and it was easy walking into her mother’s home to meet her for the first time.

“We just hugged. She was so happy to have me back,” she said.

Then she started to tell her mom about her upbringing and her family.

“She never once stopped touching me. Her hand was always on my arm or on my leg,” she said.

That was when she began to learn and embrace her culture as a member of the Dakota Sioux tribe.

“My whole life, I grew up not knowing anybody who was Native. My mom here, she did try. She had someone from the Lenape nation come to my school. But back then, I was more embarrassed by it. I was like, ‘I want to be white,’” she said.

Shannon Chase, Bashew’s sister from her adoptive family, was thrilled for her.

“The moment I realized that she belonged to them and us was when she was out there for the first time, and she called me and said for the first time in her life she looked around and everyone looked like her and she felt at home,” Chase said.

Bashew, now 58, wears beaded jewelry and T-shirts with the name of her tribe, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, and shares her story and heritage whenever she can. She has visited Sisseton 14 times in the last eight years.

Embracing Dakota Sioux Traditions

Each visit to Sisseton has taught Bashew something new about her culture.

During one visit, Bashew told her biological sister that she loved her shirt. Before Bashew left, her sister took off the shirt and gave it to her.

Many Indigenous people are socioeconomically distressed and do not have a lot, Bashew said, but they give away useful things of their own.

“Growing up… your goal is to kind of accumulate the most that you can. And that’s kind of the life I had; my dad was a dentist, we had more than most. That was very hard for me at the beginning — to give up things in order to feel more connected to people,” she said.

She has learned not to pick out a nice piece of jewelry for her mom at the mall, but to give up something that she loves.

“I looked around at the things I’ve collected and I picked stuff from there, and it’s not like I’m cheap or anything like that,” she said. “To take something of myself that I’ve loved and to give it to her is more important than me going to TJ Maxx and buying her a scarf.”

Bashew watched one of her sisters dance in a sundance ceremony on the first day of her first visit to Sisseton. It’s a sacred healing ceremony.

“I knew I wanted to do that. But it’s a hard ceremony, it’s four days of fasting, drinking, and eating, and you just dance all day,” she said.

Bashew spent a few years learning more about the ceremony and how to prepare for it, and danced her tribe’s annual sundance in 2019. She plans to dance again in 2022. She hasn’t visited Sisseton in the last two years because of the COVID-19 pandemic and her daughter’s wedding. Bashew has four kids, and they have all visited South Dakota and participated in ceremonies.

“I’m so glad to share this with them, too, because I grew up not knowing it,” she said.

Improving the Lives of Indigenous People

Bashew works as a medical biller for Jefferson Health and lives in Meadowbrook, Montgomery County. She joined the board for the Coalition of Natives and Allies in May as a volunteer.

It’s been eye-opening for Bashew to learn what she didn’t learn in school. She didn’t know about the injustices Indigenous peoples faced. Americans killed them, outlawed their religion and ceremonies, and took children from their families and forced them into boarding schools.

“Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was the flagship boarding school. And basically the government got tired of Native people trying to defend their land and stay on their land and so Col. Henry Pratt had this idea. He thought, ‘Oh, I know what we’ll do. We’ll take their children, and put them in boarding schools, and take the Indian out of them,’” said Arla Patch, a teacher and white ally in the coalition.

Only in the last few years have the remains of children who died at the school been exhumed and returned to their people.

Indigenous people did not have the right to vote until 1954.

They still struggle with poverty and face discrimination.

The coalition is currently working with state Rep. Chris Rabb (D-Philadelphia) to propose legislation to outlaw racist American Indian imagery in schools.

“We don’t want a bunch of high-schoolers running around with red paint on their chest and acting like a fool and saying they’re honoring us. That’s not honoring us, learn our history,” Bashew said.

The coalition believes proper education is the first step to defeating discrimination, racism, and disrespect to Indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups.

“Stop teaching the few pages we get in a history book in high school or grad school, and really teach what happened,” Bashew said. “It would change so much.”

The coalition is adapting a historical presentation to an elementary school level and planning to travel to a school in Hopewell Valley School District in New Jersey to teach fourth-graders about the racism Indigenous people have faced and continue to face today.

Patch said, “We want the next generation to grow up knowing the truth, and not have the misinformation that the rest of us had.”

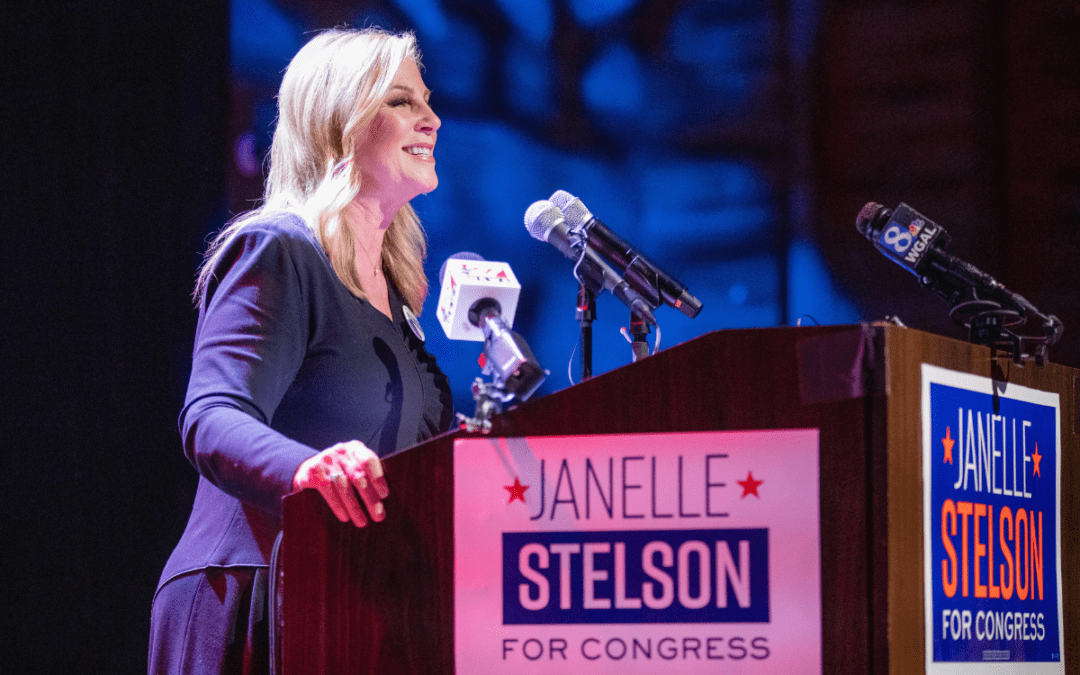

Politics

Bob Casey warns about Supreme Court’s attacks on workers and unions

US Sen. Bob Casey is warning Pennsylvania voters that the US Supreme Court is coming for the right to organize. Corporate greed and workers’ rights...

Community pushback gets school board to rescind decision on denying gay actor’s visit

Cumberland Valley School Board offered a public apology and voted to reinstate Maulik Pancholy as a guest speaker a week after the board voted to...

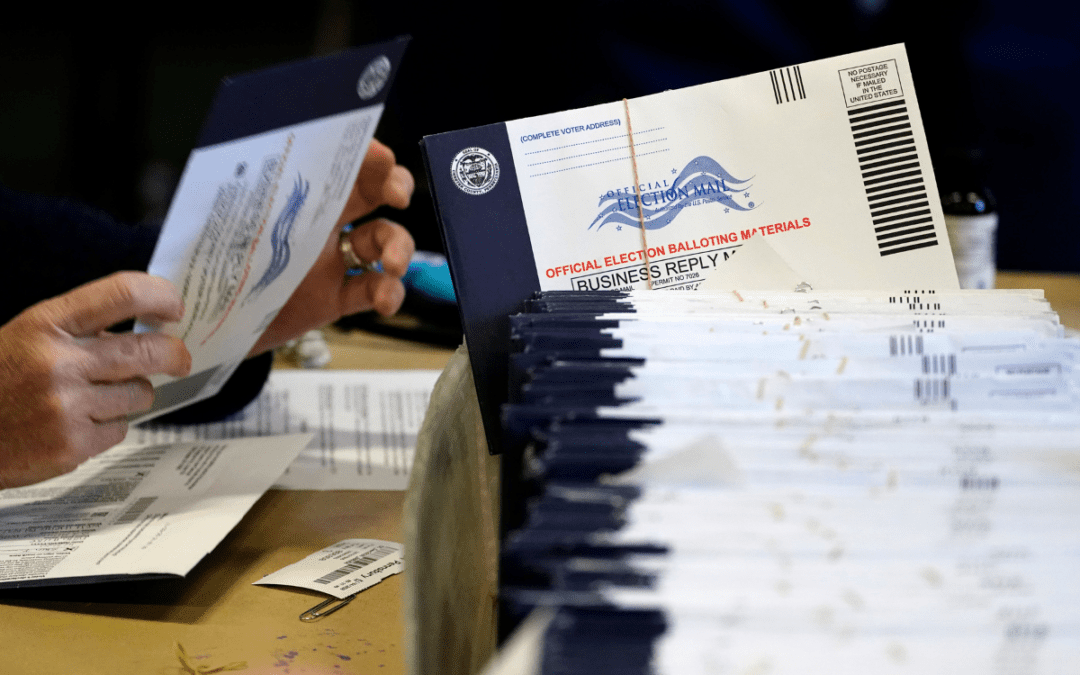

Pennsylvania redesigned its mail-in ballot envelopes amid litigation. Some voters still tripped up

HARRISBURG, Pa. (AP) — A form Pennsylvania voters must complete on the outside of mail-in ballot return envelopes has been redesigned, but that did...

Local News

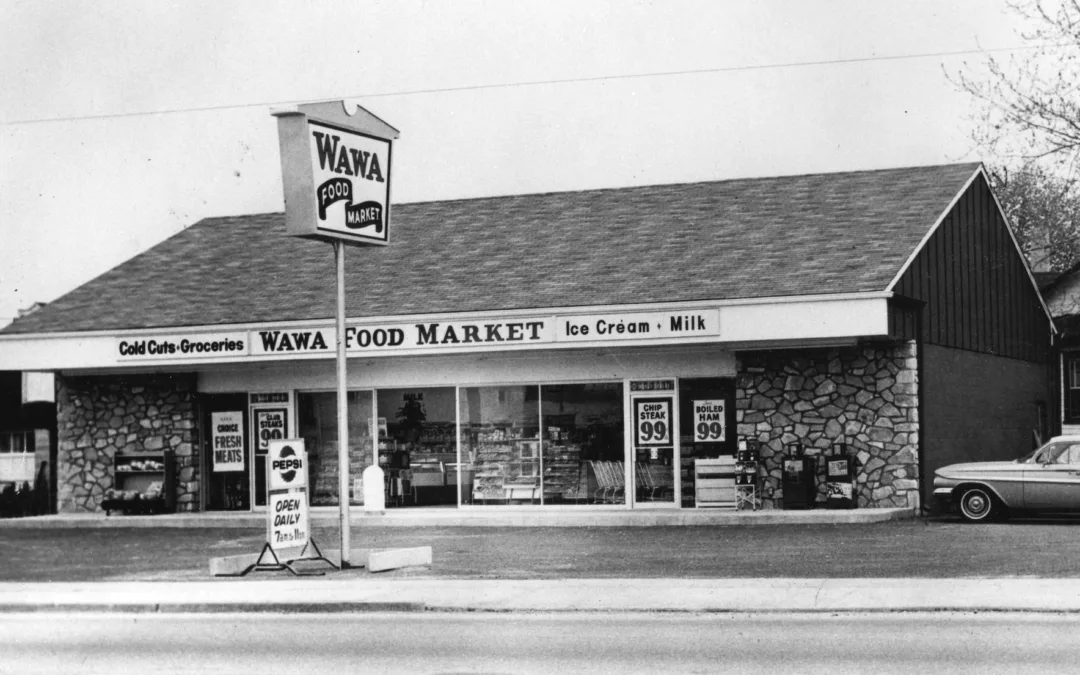

What do you know about Wawa? 7 fun facts about Pennsylvania’s beloved convenience store

Wawa has 60 years of Pennsylvania roots, and today the commonwealth’s largest private company has more than 1,000 locations along the east coast....

Conjoined twins from Berks County die at age 62

Conjoined twins Lori and George Schappell, who pursued separate careers, interests and relationships during lives that defied medical expectations,...