Harrisburg native Amanda Mustard, director and producer of the HBO documentary "Great Photo, Lovely Life." (Great Photo Lovely Life)

With the film “Great Photo, Lovely Life,” and podcast series “Trauma Town,” Harrisburg native Amanda Mustard is attempting to reckon with the trauma caused by her grandfather, a Pennsylvania chiropractor who evaded consequences for years despite being a serial child sex abuser.

In chronicling her grandfather’s history of serial sexual abuse of children — including her sister and also her mother — and the devastating toll it took on so many, Amanda Mustard wanted to avoid leaning too heavily into the heinousness of pedophilia, and how badly institutions fail victims.

To be sure, those components are featured in the Harrisburg filmmaker’s recently-released HBO documentary, “Great Photo, Lovely Life.” Mustard confronts her octogenarian grandfather, William Flickinger, in a Florida nursing home, where he matter-of-factly owns up to his abuse, stopping short of anything resembling empathy or remorse. She details how he was first charged with statutory rape of a 12-year-old girl in 1975 while working as a chiropractor in Bradford, yet only received probation and was able to carry on with his career near Harrisburg, where the abuse continued.

But Mustard felt there was a more impactful story to be mined from her grandfather’s abuse, something she said her devoutly religious family chose to sweep under the rug and “pray away” rather than deal with as she was growing up.

“I wanted to have a different conversation about what this actually looks like for families and victims,” said Mustard. “The messiness of intergenerational trauma, the messiness of keeping secrets, and what happens to a family when you decide to pull out the skeletons in the closet.”

In putting those skeletons on display, Mustard resisted portraying her now-deceased grandfather the way so many people view pedophiles: as monsters. Instead, to the extent that was possible, she sought to humanize him in an effort to show that pedophiles, at their core, are people in need of help, an issue she examines further in her new podcast series, “Trauma Town.”

“This knee-jerk response to pedophiles that we have as a society is well intentioned, but ultimately is not helpful for asking ourselves ‘How do we protect kids?’” said Mustard. “By creating as concrete of a stigma as we have, we don’t allow (pedophiles) to ask for help. And if we want to avoid the abuse of children, let’s talk about getting ahead of this. That requires humanizing pedophiles to the degree that they are human beings. They are humans that need to be held accountable, that have an issue, and what can we do to create a space for them to ask for help, and give them help? Because that is actually what protects kids. And I know that’s a hard thing for people to chew on.”

We spoke with Mustard about “Great Photo, Lovely Life.” Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

The Keystone: How were you able to separate filmmaker from survivor, and maintain the objectivity to assess your work critically while telling your story and protecting yourself emotionally?

Amanda Mustard: It was weird. Approaching this, I was very aware of my objectivity, or lack thereof. I had a fantastic co-director, Rachel Beth Anderson. It was really important for me to have her as a filter. After we would film things — I’m so normalized to it, I’m just talking to my family — I’d look at her afterwards and say, ‘What was that to you?’ I needed this interpreter who could help me see the things that I couldn’t see. And to keep me in check as well. Having that partnership was really critical. Just being aware of that was really important. I didn’t want the story to be about me either. I’m the guide through it. Ultimately, it’s my story, but it isn’t. It’s more my family’s.

In the podcast, you talk about the exhaustive effort of trying to find financing and a home for a project that is so uniquely personal and sensitive. What was it like for you to process feedback?

I really resented that process and I tell people, honestly, the most traumatizing part of making this was the fundraising process. Hands down. Because I knew what I wanted to say, I had the ability to say it. But having to essentially sell your family’s trauma and go through live pitches, and grant applications, and being rejected by every single grant we applied to in America for four years, it was really, really brutal. But at the end of the day, I’m so glad that we ended up with HBO, because they were the first platform that looked at it and said it was a no-brainer. They saw the vision and the value of the message.

I think the film does a tremendous job of humanizing your grandfather, thereby exposing what I think you accurately identify in the podcast as psychopathy. How do you think he saw himself?

Unfortunately for my grandfather, by the time I talked to him, he was in his 80s. He’d gotten away with it and absolved himself, and created this horrifying maze of absolution for himself. I’m not confident that he’s someone who wanted help or could have been helped. I think there were layers, more than just his attraction to children. To be able to help people like that, we need to get comfortable with discomfort, and get away from this knee-jerk reaction that people have over this outrage. My whole goal with this film was to move us just a little bit closer to that place. It’s not a conversation that a lot of people are having. But there are people who are. The Moore Center for Child Sex Abuse Prevention at Johns Hopkins is having this conversation. The research is there.

What did your inbox look like once the film was out there?

The inbox has been very full, more than at any other point in my adult life. It’s mostly people who are very grateful, and feel seen in a way they haven’t before. Which is why I made this. I’m horrified that there are so many of them, but also glad that they feel seen. Because so many people carry this in silence and feel like they’re the problem, or they’re crazy. It’s like, ‘No, you’re not crazy. It’s just this is really, really hard and people are bad at talking about this. The reaction has been very overwhelmingly positive. There are some people who are very mad, and don’t know what to do with their anger, which I understand. They’ll take it out on my grandma or my mom, or me, for responding or reacting in a way that they don’t approve of. I’m like, ‘I’m mad about the lack of justice. I’m mad about the lack of accountability too.’ But we wanted to be honest in what this looks like. Personally, I’ve had to work through that anger for years.

How do you feel about the ongoing saga over the statute of limitations for sexual abuse surivors in Pennsylvania? Twenty states have reformed their statutes and extended the windows for survivors to take legal action against their abusers, while Pennsylvania is still struggling to do so due to Republicans playing games with packaging amendments.

I have so much respect for Rep. Mark Rozzi’s fight for this. It’s really disappointing that Republicans are stepping in the way of countless survivors being able to receive the acknowledgement or justice they deserve. The side you’re on directly speaks to who they are protecting. It can take a lifetime to come to terms with the harm caused to you as a child, and revival windows or other statute reforms are the least we can do to give them the ability to press charges — if they want to, and when they’re ready to.

“Great Photo, Lovely Life” is streaming now on Max.

Politics

Biden makes 4 million more workers eligible for overtime pay

The Biden administration announced a new rule Tuesday to expand overtime pay for around 4 million lower-paid salaried employees nationwide. The...

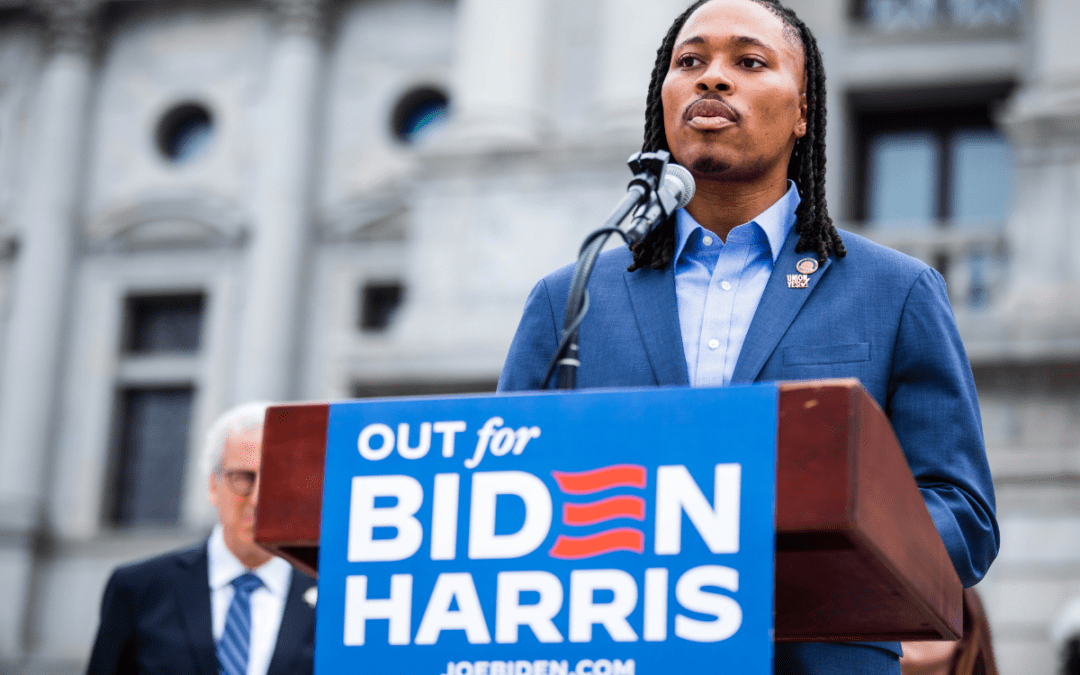

Malcolm Kenyatta makes history after winning primary for Pa. Auditor General

State Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta, who was first elected to the state House in 2018, won the Democratic nomination for Pa. Auditor General and will...

Biden administration bans noncompete clauses for workers

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted on Tuesday to ban noncompete agreements—those pesky clauses that employers often force their workers to...

Local News

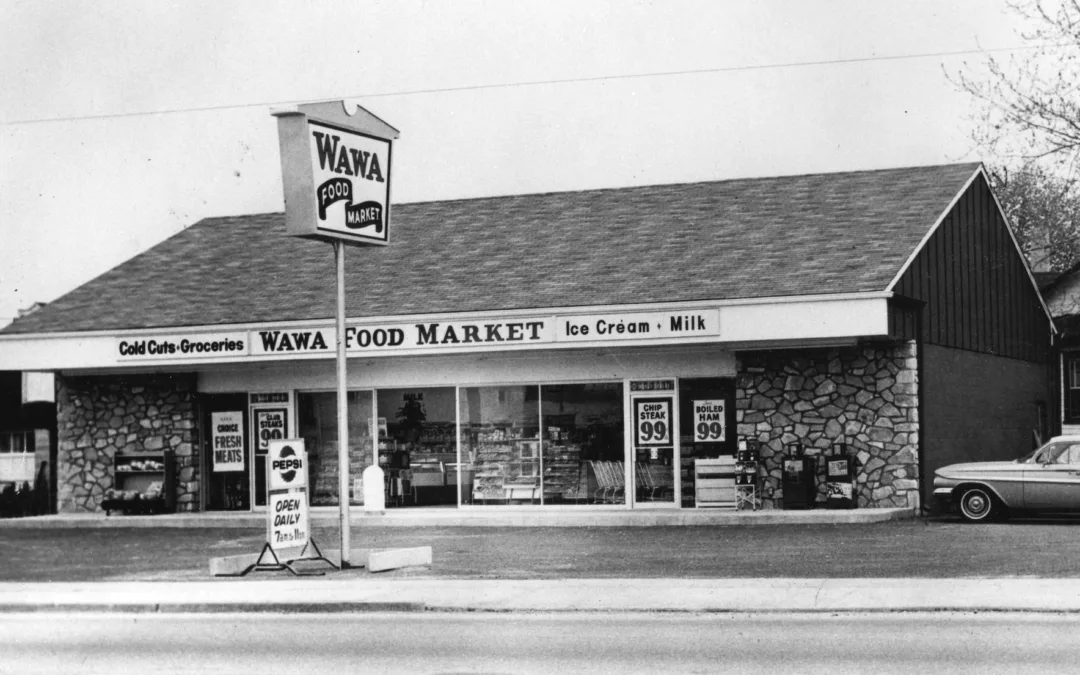

What do you know about Wawa? 7 fun facts about Pennsylvania’s beloved convenience store

Wawa has 60 years of Pennsylvania roots, and today the commonwealth’s largest private company has more than 1,000 locations along the east coast....

Conjoined twins from Berks County die at age 62

Conjoined twins Lori and George Schappell, who pursued separate careers, interests and relationships during lives that defied medical expectations,...